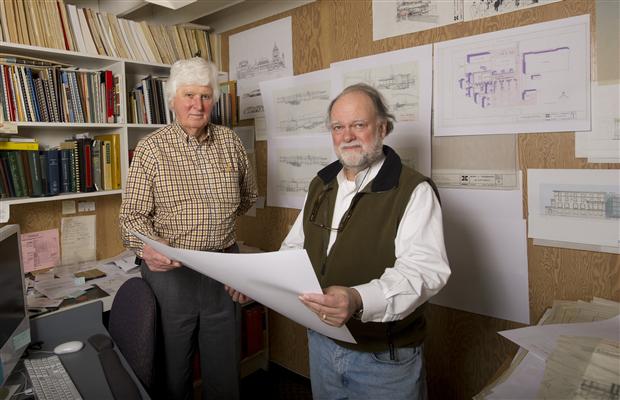

Art historian Martin Segger, right, curated a show that highlighted mid-century Victoria architects, including Alan Hodgson, left, circa 2011. Photo: FRANCES LITMAN / VICTORIA TIMES COLONIST

SOME OBSERVATIONS AND THOUGHTS ON THE CAREER OF ALAN JAMES HODGSON F.R.A.I.C ARCHITECT (1928-2018)

by Martin Segger

Delivered at his Celebration of Life, Union Club of British Columbia, August 12, 2018

Sheila Hodgson kindly invited me to say a few words about Alan’s legacy as a Victoria architect during Alan’s celebration of life held at the Union Club. And I am delighted to do so…

It is appropriate that we are here at the Union Club of British Columbia celebrating Alan’s life. As well as a member, he was for many years architect of record for the maintenance and improvement of this Club house. Members owe him a debt of gratitude for his diligent stewardship of the fabric which laid the groundwork for the more recent total restoration of the Club, including the room we are in …. finishing touches now being applied!

My own introduction to Alan’s work was rather curious. I first became familiar with one of his masterpieces, the MacLaurin Building at the University of Victoria. I was an undergraduate at UVic participating in a week-long student protest sit-in outside the president’s office on the fourth floor. Another major project, Centennial Square, was of course the gathering point, also for seemingly all too frequent student protest marches on the Provincial Legislature. This also was shortly to become one of his major restoration projects. Although, of course, at the time we didn’t pay much attention to the architecture.

My real familiarity with his work was to come much later, as a co-supporter and activist in heritage conservation. And more recently with a more academic focus on appreciating Victoria’s early Modernist legacy. I treasure so many conversations with him on that topic. He was a marvelous raconteur on the subject of the post-war architectural practices in Victoria.

Alan’s architectural career was multifaceted. After opening his own practice in 1960, Alan quickly developed a reputation for his very personal interpretation of the current International Modernist idiom. In his residential work he was an early exponent of the West Coast Style. The Hodgson family’s own house in Vic West, the sculptor Elza Mayhew’s studio in James Bay and the Warren House in Saanich, are all sublime essays in site-specific design, expressions of local materials, sophisticated manipulation of natural light, open floor plans and glazed walls framing dramatic view-scapes. One has to put them in a category along with the contemporaneous work of the Vancouverites Ned Pratt and Ron Thom. And I would argue that there was something very uniquely Victoria about Alan’s domestic work, a scale and respect for location and setting that eschewed, for instance, the more dramatic bombast of Arthur Erickson’s houses on the North Shore of Vancouver at that time.

The application of these same sensitivities on a larger scale was evident in Alan’s early institutional work.

Engaged in 1966 to carry-out the largest commission in the first phase of the University of Victoria’s new Gordon Head Campus, Alan designed the six-story Arts and Education (MacLaurin) Building. His design brief stated that the building must create a “progressive social atmosphere, one that encouraged students to meet and interact with each other”. And in response he designed a massive concreted structure that, elevated above ground level on pilotis, allowed for a mix of open public spaces, external arcades and interior glazed galleries focusing on a contained but open courtyard. The Corbusier-inspired concrete Brutalism of the forms and finishes is softened with the use a warm red-brick finishes and reticulated cedar window hoods on the south-side upper floors. This blends with a Scandinavian attention to detail and finish carried throughout the interiors. The MacLaurin set a high standard that would be echoed during subsequent phases of the University’s build-out over the next 50 years. In 1971 and 1978, Alan provided additions to the building, including the Music Wing comprising practice rooms and teaching spaces anchored by the Phillip Young Auditorium still noted as one of the finest acoustical performance halls in Victoria.

This project no-doubt led to another major educational commission, the Terrace campus for Northwest Community College (now Coast Mountain College) in 1968. Here a range of classroom buildings anchored by a large student services block respond to their woodland meadow setting on a coastal mountain plateau. The buildings, studies in abstract form, explore the play between cast concrete structural elements, wood-detailing and cedar-siding wall panel finishes.

Alan’s innovative use of concrete, brick and glazed curtain wall found early expression in his work along with another interest. In 1961 he joined with the group of local architects lead by Rod Clack responding to Mayor Richard Biggerstaff Wilson’s 1961 call to revitalize down-town Victoria by creating a “progressively modern” civic square. Alan and Rod worked together on the architectural model which laid out the design approach and main elements of the Square. The project included the restoration of two major civic monuments, the 1878/91 City Hall and 1914 Pantages Theatre, while adapting both to a new life as part of an active pedestrian space. Alan’s piece, the theatre project, prompted extensive research in Europe that ultimately lead to a faithful restoration of the historic audience chamber, but also a new back-stage, front-of-house lobbies and a restaurant addition raised above the Square. The Modernist additions utilizing cantilevered reinforced concrete elements, brick façade finishes and expansive glazed curtain walls gracefully transitioned the east end of the Square from the Victorian urban setting of Old Town to the spirited Modernism of the new Square, particularly its central focal point, the mosaic stele of Jack Wilkinson’s “Centennial Fountain”. Centennial Square was recognized with an AIBC Award for Architectural Excellence.

While completing his articles at Public Works in the late 1950s, Alan worked with Peter Cotton and Andy Cochrane on the new Government House. Replacing the previous Rattenbury/Maclure Arts-and-Crafts style building which burned down in 1957, this design referenced its institutional heritage with a modern evocation that maintained the functional floor plan of the original. It also recreated in-detail, the main state rooms of its Edwardian predecessor. Heritage restoration was to become a major specialization within Alan’s practice.

The Pantages Theatre project was followed by what was to become the largest heritage restoration project in the Province. In the early 1970s Alan assumed the roles of design and project architect for the restoration of the Parliament Buildings. He was awarded the prestigious Heritage Canada National Conservation Award for nearly two decades of innovative conservation work on the Buildings. This not only included a faithful restoration of the major ceremonial spaces, training a new generation of restoration craft trades, but also – based on detailed study of the original F. M. Rattenbury drawings – a highly innovative “finishing” of previously undeveloped areas of the buildings according to Rattenbury’s original intentions. Numerous high-profile architectural conservations projects would follow: for instance, the Victoria Masonic Temple, the Odd Fellows Hall, and the conversion of an Edwardian temple bank into Munro’s Bookshop, the latter celebrated with a Hallmark Restoration Award.

Alan’s practice was noted for the quiet elegance and attention to detail in the design work. This can be seen in his commissions, over 500 during his 55 years of practice. These included the industrial plant complex for Island Farms Dairies on Blanshard Street, marking the entrance to downtown Victoria, to his churches from the restoration of the chancel at St. Saviour’s Anglican to a new building for the congregation of Cadboro Bay United Church.

I should add that over the years a number of his commissions were brilliantly documented by the well-known Vancouver architectural photographer, John Fulkner. Fulkner’s photo archive was recently accepted into the permanent collection of the West Vancouver Museum.

Alan was a leading influence in his profession during the formative years of post-war Modernism on the West Coast. He was deeply respected by his peers, a fact signaled by their election of him as a Fellow of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada in 1998. He was a mentor to many students, in particular those he taught during his three-year appointment as associate professor at the UBC School of Architecture where along with a small group of faculty he pioneered the overseas study tours. The first one to Venice is now institution at the school.

In concluding, I’d like to prompt you to contemplate the fact that downtown Victoria is bookended by two of Alan’s projects that both ran almost the length of his career. And they couldn’t be more different. At one end, on Blanshard and Bay Streets, the Island Farms Dairy: a large-scale industrial plant. At the other, on the harbour, his 40 year plus restoration project, the Parliament Buildings. At the Dairy, an essay in high modern functionalism, a series of abstract cubist forms achieves an almost magical disappearing act for such a massive imposition … his response to a very sensitive location marking the entrance to Victoria’s urban core. In contrast, of course, and thanks to Alan, the monumental Parliament Building today still hold their own at the City’s harbour front entrance.

Alan’s work is a testament to his passionate vision for good design, always inspired by both a fine-grained sense-of-place, and a radical humanism.

Martin Segger, B.A., Dip. Ed., M.Phil.

University of Victoria | UVIC – Department of History in Art