In this rare glimpse inside the BBC archives, we reveal the exasperated internal memos, the furious letters from wing commanders – and David Frost’s bid to bring them down.

In a memo sent in 1969, the BBC head of comedy seems to have lost his sense of humour. “Please will you have a word with the writers?” said Michael Mills. “I haven’t reacted to the funny titles that have appeared on the scripts so far. I hoped that they would cease of their own accord.”

The titles that irritated him included “Bunn Wackett Buzzard Stubble and Boot”, apparently a spoof legal firm, which came to be shortened to Bunwackett. The show, meanwhile, had the working title The Circus. Now, though, Mills had had enough: “The time has come when we must stop having peculiar titles and settle on one overall title … Please would you have words with them and try to produce something palatable?”

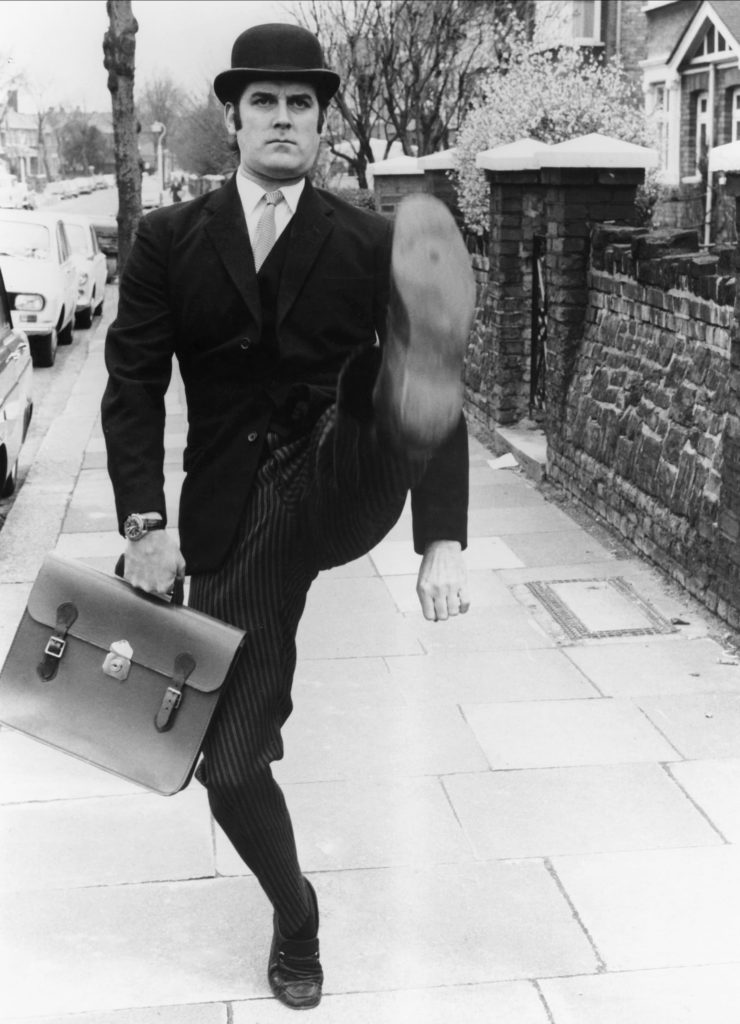

Following this intervention, a title was finally agreed upon: Monty Python’s Flying Circus. And on 19 September 1969, BBC North sent an invitation to journalists to go on location for the filming of the show at the Cow and Calf pub on Ilkley Moor. They were promised “crazy antics” and “the first opportunity to see this new-style brand of late-night nutty comedy in action, and all its writer-stars: John Cleese, Terry Jones, Eric Idle, Graham Chapman and Michael Palin.” (As would often be the case, the animator Terry Gilliam was omitted, though he played many on-screen roles, and his brutal cartoons were the show’s signature innovation.)

This memo and press release are among the documentation relating to the premiere, exactly 50 years ago, of Monty Python’s Flying Circus. Until exhumed by a researcher, the creative entrails of old BBC shows are buried in pink folders, hole-punched and tied with green bootlaces. Now, a rare peek inside the binders has uncovered all the secrets of the Pythons’ earliest days.

The archive is especially important for this show. The Pythons included a prolific diarist – Palin has published three hefty volumes already – but, dismayingly, the months around the start of the first Python show are one of the longest gaps. Palin attributes this to the busy-ness of filming, and having a young child and ailing elderly father.

Presumably following calculations on some abacus of celebrity value, accounts initially paid Cleese £67 per show more than the others, Palin £1 less than Jones and Chapman, and Idle £2 less. Gilliam, an artist rather than “artiste”, was contracted separately.

Although comic weirdness had been introduced to the BBC by The Goon Show, Monty Python went even further. BBC production teams may have sensed something odd was coming from the paperwork: a requisition form to the props department asks for a “selection of bras (6), panties (6), and tights (5)” and “1 swastika flag, approx 4’ x 2.6”. A list of extras for a filming day includes, after one name, the specification “no pigeon on shoulder” (parrots, on shoulders and flat on their perch, would become a Python speciality). A handwritten note asks: “What about topless on fountain?”

Most surreally, on 9 September, the show’s producer John Howard Davies sent a memo to Bernard Wilkie in visual effects requesting “1 copy of Turner’s ‘Fighting Temeraire’ … in a detachable frame, which can be broken off and eaten – with two eatable refill frames”.

Later the same day, Wilkie’s assistant returned the request with the note: “Unfortunately … all edible props must be obtained through the Catering Manager.”

While the head of comedy had persuaded the team to pick a title, he could not persuade them to take editorial procedures seriously. The Pythons wanted to caption the first episode “programme two”, a joke the corporation chose to ignore. They also described their show as “designed to subdue the violence in us all with gentle sick laughter”. This was not passed on to the press, though the misleading subtitle “Wither Canada?” was – which some newspaper previews reproduced unquestioningly.

Having survived the threat of a strike by BBC staff over the controversy that the new comedy show was replacing a late-night religious programme – the corporation cleverly argued that the devotional show was shifted to spare clergymen a late night on their busiest day – Monty Python’s Flying Circus was first transmitted at 22:50 on 5 October 1969.

A memo sent between senior executives reveals that the first episode achieved 1.5 million viewers with an audience appreciation (based on a small number of viewers paid to value what they watched) of 45 (out of 100). In comparison, the Rolf Harris Show (though in a primetime slot, and with a presenter then seen as a lovable family entertainer, rather than the convicted sex offender he later became) attracted 11 million viewers and a 64 enjoyment score.

The public response, at least from the correspondence archived by the BBC, seems to have been positive. The fan letters are a rarity, in that they immediately mimic and celebrate the tone of the Pythons. What seems to be a furious letter from a wing commander (retired), complaining about the “long-haired louts” making fun of the flying machines that won the Battle of Britain, is revealed to be written by a 16-year-old called Philip.

Another viewer called Rufus writes in the guise of an expert in the art or sport of “black pudding bending”. A gentleman from Tunbridge Wells is not outraged, in line with the local stereotype, but engaged, repeatedly sending handwritten sketches that are politely declined on the grounds that the Pythons write all their own material.Advertisement

While Cleese has latterly attracted a reputation for irascibility, he is caught out in the files in a gesture of striking kindness. A Kent schoolboy called Doug Holman writes, asking for tickets to a recording. Cleese arranges for a pair to be sent. Doug, boldly, writes back, saying he is part of a large group of friends who want to go. Cleese contacts the BBC to request a further 14 tickets, suggesting that the young will be “good laughers”.

Given the passage of five decades, many of the early Python audience have joined the choir invisible with the programme’s late parrot. But I tracked down a Doug Holman who grew up in Kent and is now 69, running a business in Hampshire. My email rapidly received the reply: “It’s a fair cop! Hearty congratulations on your detective work.”

In 1969, he was an electronics student at Portsmouth University, and an obsessive fan of the radio show I’m Sorry I’ll Read That Again, starring Cleese. Noticing a poster in the student union advertising the comedian as guest speaker, Holman went and saw Cleese deliver a “verbal assault on British Rail [he had arrived late] and BBC bureaucracy”, before inviting the students to write to him if they wanted tickets for a recording of I’m Sorry I’ll Read That Again.

Then, “almost as an afterthought,” Holman remembers, “he handed round a few copies of scripts for ‘a new, as yet untitled, TV show’ he was hoping would be commissioned. The copy I saw included strange references to things like exploding knees, but I confess the general reaction was one of polite perplexity.”

Holman wrote off for tickets to the radio show but, some days later, “my sister rushed into the kitchen blurting out: ‘It’s … John Cleese … from the BBC … for Doug!’ Cleese explained that sadly, there would be no new series of ISIRTA that year, before asking whether I’d be interested in tickets for the new TV show? In the heat of the moment, I suggested: ‘How about four; that’s four car-loads?’ That’s why the number of tickets increased from two to 16.”Advertisement

The BBC response, the archives make clear, was far less positive. At the weekly meeting where senior managers discussed the output, the head of factual had found Python “disgusting”, arts had thought it “nihilistic and cruel”, while religion objected to a Gilliam animation in which “Jesus … had swung his arm”. The BBC One controller sensed the makers “continually going over the edge of what is acceptable”.

In yet another sign of internal disapproval, the Pythons were commissioned to provide material for the 1969 Christmas Night with the Stars, the BBC end-of-year jamboree, but a brisk memo rejects their sketch.

The archives also reveal an undertow of tension with the TV presenter and producer, David Frost. On 20 April 1969, while the first series is in pre-production, the writer-performer Barry Took, then a consultant for the BBC, warns Mills, the head of comedy: “John Cleese phoned today to say that he is still under contract to Paradine Productions, who want to be involved in The Circus project as a co-production.”

Frost, only 30 but already a formidable TV impresario, owned Paradine (which was called after his middle name). Took reports that, if the BBC will not co-operate with Frost, Cleese will withdraw from The Circus. He recommends that the BBC produce a series with “Palin, Jones, Idle and cartoon inserts from Terry Gilliam”, then revive the idea of The Circus in 1971, when Cleese becomes free.

There is always a moment when what is now a classic comes perilously close to not happening; this was Python’s. The files do not reveal how the BBC saw off Frost, but the corporation seems to have played hard-ball.

In another intrusion of real-life surreality into the Python story, the postmaster general at the time was John Stonehouse, who would soon afterwards fake his death by leaving his clothes on a beach in Miami, and was subsequently arrested by police officers who thought he was Lord Lucan, another prominent disappeared Briton of the era. Stonehouse was jailed for fraud, and revealed as a Czechoslovakian secret agent. Having censured Python over the Frost incident, he later inspired another major BBC comedy series: The Rise and Fall of Reginald Perrin, in which David Nobbs’ hero pretends to have drowned in a swimming accident.

On 11 August 1970, having commissioned a second run of Python, Mills laments in a memo to the BBC hierarchy: “I am very unhappy that all the regions are opting out of the new series.” The team had become victim to another BBC continuity announcement trope they liked to satirise: “Except for viewers in Scotland/Northern Ireland/Wales.”

But these rejections – and many memos reporting Cleese’s reluctance to make another series – could not prevent the Pythons going on to conquer TV, cinema (Holy Grail, Life of Brian) and stage.

Five decades after a 19-year-old student struck the audacious free-ticket deal immortalised in the BBC archives, Holman still energises his memories of the recording: “There was a restaurant scene but I think the producer abandoned it when Cleese – seemingly unhappy about having no lines – disrupted each take by performing random Tourette-like impressions of a mouse being strangled by a psychotic cat. I remember it being total anarchy yet excruciatingly funny, in the literal sense. We all experienced genuine pain from extended bouts of uncontrollable laughter.”